Why are the Streets Built This Way? The Curb Cut

There was a time not all that long ago that every corner had a solid curb, creating a few-inch drop to the street. This is a single step for someone walking. It is a barrier for someone with a wheelchair.

After World War II (1939-1945), the issue of curbs being a barrier in the center of town began to get attention. It was not feasible for veterans of the war to be expected to use driveways to get off the sidewalk, then travel in the street to the nearest driveway across the street. Veteran Jack Fisher advocated and got the first curb cuts for mobility in the retail areas in Kalamazoo, Michigan in 1945. [Source: Carleton.edu]

The movement for curb cuts escalated when Ed Roberts, a man using an iron lung because he had polio, led protests in Berkeley California. His advocacy led to expansion of the Architectural Barriers Act. Eventually, in 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act compelled Americans to build with universal design, so that people with mobility impairment could access public areas in a town or city.

1945 curb cut:

Photo Source: https://mosaicofminds.medium.com/the-curb-cut-effect-how-making-public-spaces-accessible-to-people-with-disabilities-helps-everyone-d69f24c58785

Photo Source: https://mosaicofminds.medium.com/the-curb-cut-effect-how-making-public-spaces-accessible-to-people-with-disabilities-helps-everyone-d69f24c58785

Curb cuts did not start out as good for everyone

Curb cuts, as they were used in 1945, created a problem for blind people. Were a blind person to walk down a street with a curb cut at the corner, they would have no way to feel that they were entering a street. Blind people depended on feeling the curb to know that an intersection was ahead. This problem was solved by Seiiche Miyake in 1967. Miyake invented a tactile tile, called Tenji blocks — Tenji is the Japanese version of Braille — that can be embedded into the sidewalk, so that blind people can feel their way along walking routes. This solution had been incorporated into ADA standards by the 1990s.

Universal design curb cuts use tactile domes or tenji blocks. That way, wheels are not stopped at the curb, but blind people remain aware that they are entering a street. If you travel around most cities and towns, you will notice curb cuts with tenji blocks. There are also tenji blocks along the edge of train platforms and other drop-offs. They are just part of the landscape now. Curb cuts that have tenji blocks help people in wheelchairs a lot. The addition of tenji blocks made them safe for blind people.

Universal design curb cuts use tactile domes or tenji blocks. That way, wheels are not stopped at the curb, but blind people remain aware that they are entering a street. If you travel around most cities and towns, you will notice curb cuts with tenji blocks. There are also tenji blocks along the edge of train platforms and other drop-offs. They are just part of the landscape now. Curb cuts that have tenji blocks help people in wheelchairs a lot. The addition of tenji blocks made them safe for blind people.

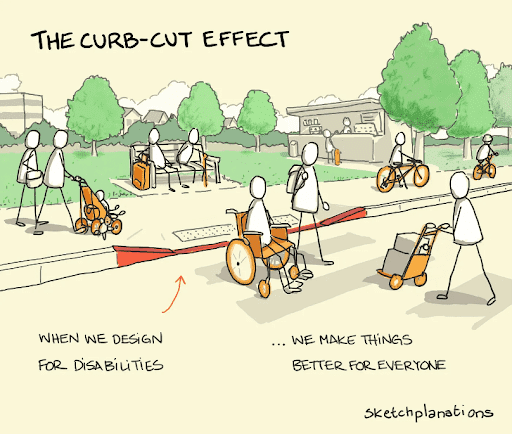

What is the curb effect?

Changes to cities and towns that benefit one group sometimes have a side effect of being better for people more generally. When curb cuts and ramps became more common, they benefited people who used strollers or carts. People with temporary mobility problems, like using crutches after an injury, also benefited.

Another example of the curb effect that has nothing to do with streets

Have you noticed the captioning option on your streamed video and TV services? Those help deaf people access video. The captions became a “curb effect,” because now you see captions on TVs in bars and restaurants; this helps people follow TV in noisy places.

Captions help people learn English by reading what the English speakers are saying. They help people practice other languages, too, since some video is captioned in more than English. It helps children practice reading. Some people with normal hearing use captions because the people on TV have accents that they can’t follow.