A Modest Proposal: Reparations and a New GI Bill

Fair Housing is where my professional life and my political life intersect. I am a residential real estate broker, and also a member of the Somerville Fair Housing Commission. What I am writing about, just below, is being said with neither of those hats on my head. It is from my life experience.

What I sort of knew all my life — but directly learned as an adult — is that the way that my family went from poor immigrant laborers to professional class was not by consistent work alone. It was consistent work, union membership, and the G.I. Bill.

My white family benefited from both educational and housing opportunities that were available to us but not available to Black families. (Many unions were restricted, also, but that is another story for another day.) When my father returned from the Air Force at the end of World War II, he was able to purchase a house in a town with a good school system. Even though he did not use the college benefits – he was a laborer all his life — the G.I. Bill made a significant difference for my generation. A veteran who was Black would not have been able to buy in this town, due to housing and mortgage discrimination. Many colleges did not admit Black students in my father’s time.

I learned, as an adult, that the housing that Black families could buy was zoned near to industrial areas. It was more expensive – not cheaper – than what was available to my father and mother. This housing was less desirable because it was polluted. It increased in value more slowly, or not at all. That “American Dream” of building a future on housing was just not available to Black veterans the way it was to white veterans.

My proposal for a new GI Bill:

Reparations can begin by a reboot of the G.I. Bill. Mortgage and housing benefits would go to any person of color who had an ancestor who could not benefit at the time the Bill was passed. It may be feasible to include all service members and their descendants since the end of World War II, except those who used the benefits in the original G.I. Bill.

The G.I. Bill is often credited for the prosperity of the 1950’s and 1960’s. When military personnel returned to civilian life, they flooded the job and housing market, causing severe employment and housing shortages. The G.I. Bill poured money into housing, education, and industry. Natick — right here in the Boston area — is a perfect example. It looked like suburbs all over the country.

Now, I am putting on my Fair Housing Commissioner hat:

Please join the Fair Housing Commission for an in-person or Zoom event this month to discuss the video Segregated by Design or the book The Color of Law. I learned so much from Richard Rothstein’s work that I created these programs to share it!

A brief history of the GI Bill and housing discrimination in the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s

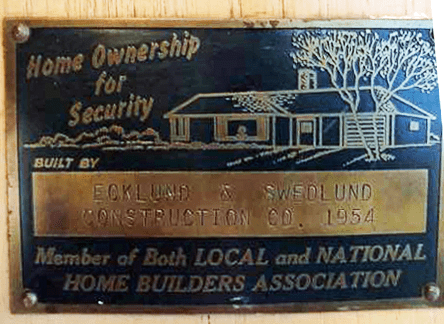

After World War II, the United States government created The Servicemembers’ Readjustment Act of 1944, an economic stimulus package commonly called “The G.I. Bill.” This bill boosted housing development by offering housing incentives to builders and mortgage incentives to veterans.

There were also educational benefits, which supported college and vocational training for people who served in the military during the war. By 1956, roughly 7.8 million veterans had used the G.I. Bill education benefits, some 2.2 million to attend colleges or universities and an additional 5.6 million for some kind of training program.

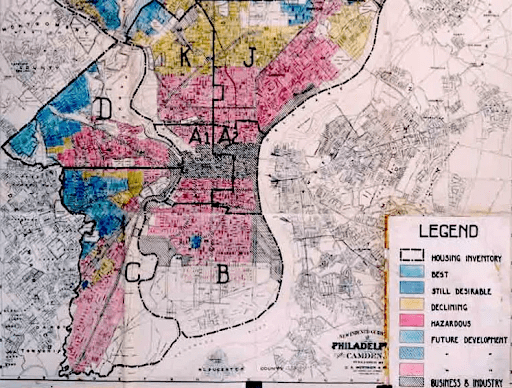

In these years, Jim Crow segregation laws were still in effect. Redlining was common. (Redlining is a pattern of lenders rejecting mortgages for properties in specific “declining or “hazardous” neighborhoods. Named for the practice of drawing a red line drawn around these, mostly minority, hazardous neighborhoods.)

The effect of redlining was that many African Americans could not benefit from no-down-payment, low rate G.I. mortgages in neighborhoods where other African Americans lived. In many parts of the country, African American could only live in African American neighborhoods, due to segregation and social patterns of racism. G.I. starter homes, like the 17,000+ Levittown houses across America, were restricted to Whites only. So were many other, less well-known housing developments.

The G.I. Bill made it possible for white veterans to buy houses. Racial housing discrimination restricted many Black veterans from doing so. Of the first 67,000 mortgages insured by the G.I. Bill, fewer than 100 were taken out by non-whites.

(*Source: Katznelson, Ira (2006). When affirmative action was white : an untold history of racial inequality in twentieth-century America.)

White veterans who bought starter homes in the 1950s had a foothold into housing appreciation. The cost of housing is typically 25-33 percent of household income. Housing appreciation is an exceptionally good way to build assets. It turns the cost of housing into a commodity that can be resold at a profit, most of the time. Renters pay for housing and do not gain assets.

Fast-forward two generations or so. The latest figures from the U.S. Census Bureau show the median net worth for an African American family is $14,100, compared with $150,300 for a white family. Latino families did not fare much better at $31,700. If you add housing equity, white households had an average of $56,250, while Black households had $3,630 and Hispanic households had $9,600.

Now, I am putting on my Real Estate Broker hat:

“National housing production jumped from 140,000 units in 1944 to a million in 1946.” Can you imagine how another wave of that kind of production would solve the housing problems that are plaguing us?