Roads, bridges, and public safety

This has been a week when I ponder how much I depend on the government to do physical tasks for public safety. This is a thank-you for all the workers who maintain the roads and bridges I walk and drive on.

On January 28th, I moved my car off the street, while my neighbors did the same, or parked on the odd side of the street. We expect — really demand — that plows will be coming by to make our roads passable (especially for emergency vehicles) within hours of the end of the storm.

As we dug out, the complaints poured into local officials where plowing was insufficient. This year, I was a complainer. For the first time in memory, our corner was not cleared well enough for cars (let alone fire trucks) to get through. I sent a tweet, and the plows cleared it. This is a miracle made possible by my tax dollars. Somewhere, there is a person who I will never directly thank for working long hours last week.

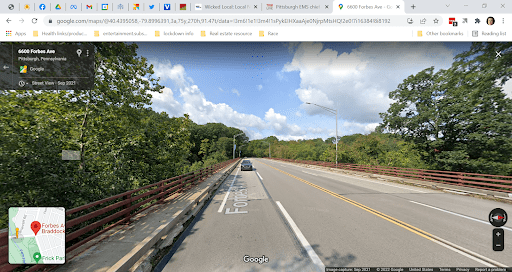

The bridge in Pittsburgh

The depths of my gratitude was increased because of the recent bridge collapse in Pittsburgh on January 28th. It made me more acutely aware that there is someone, somewhere, who has the job of keeping roads open for our use. It made me aware that I have always depended on government to create and maintain roads.

Our national lesson this week is that when we neglect our infrastructure, disaster follows.

The Fern Hollow Bridge in Pittsburgh normally carries about 10,000 cars a day. When it collapsed around six in the morning, one bus and a few passage vehicles were on it. Because of the time of the collapse, there were no deaths.

I am a Pittsburgher by marriage. I first visited the city in 1986. There was still a steel mill along the river. It had already changed beyond recognition to the locals; it’s changed a lot since then, too. It is a city with a lot of hills, and a lot of roads that run over valleys.

I have had family (by marriage and love) there since that time. I also have a nephew (my brother’s son) who moved there in 2016. His love for former industrial cities took him from Connecticut to Buffalo, and then he chose Pittsburgh. I caught some of my love of old industrial architecture from that nephew. I also notice how hills in Pittsburgh shape the city more than those around Boston.

Because of multiple trips to Pittsburgh, I know Forbes Avenue. I know that bridge section. It is near the part of Pittsburgh where most of my in-laws live. I have walked there. I have driven there. I have grumbled at the stop-light on the corner of Forbes and South Braddock.

Maintaining a national roadway

In 1956, The Federal-Aid Highway Act funded an interstate highway system that connects the country for motor vehicles. Most people in America depend on these highways for personal use, as well as the goods that are trucked into town. The cost was big, but the return is estimated at $6 in commerce for every dollar that was spent.

The cost was $56 billion dollars. It created a network of highways that connect major cities throughout the country; 41,000 miles of highway. The Federal government carried the cost of 90 percent of the construction by increasing gasoline tax.

That was more than 60 years ago. Since then, the Federal government continues to support states through the FHWA to the tune of about $50 billion dollars a year. That’s what it costs to keep good pavement on those 41,000 miles of roads. Bridges, however, are part of the budget from state and local governments. Bridges are subject to freezing and heating, rain, snow, and ice. Their roadways are treated with corrosive materials to clear away ice.

We depend on someone to plow the roads. We expect that resurfacing will happen before highway potholes cause accidents. We expect that bridges will be maintained so that they don’t collapse. These services are necessary to keep us connected to people and goods. They are paid for by a combination of government bodies on different levels of government.

Notable failed bridges:

In 1983, a 100-foot section of bridge that was part of Interstate 95 in Connecticut collapsed in the middle of the night. Three people died, and three were injured. That bridge regularly carried 80-90,000 vehicles a day. The cost to rebuild and reroute traffic, in 1983-dollars, was $37 million.

I remember when I read about this bridge collapse. Like the Pittsburgh bridge this week, I have memory of driving over that bridge. So I took it personally. I easily could have been there, driving around midnight through Connecticut.

Disaster that didn’t happen:

Even when they don’t fall, the cost of rebuilding can be staggering. In 2007, it was clear that the Longfellow Bridge was in need of rebuilding. When all the expenses were added up, the rebuilding cost $303.7 million, in 2018 dollars. The bridge, according to MassDOT, carries 28,000 motor vehicles and 90,000 transit riders per day, along with pedestrians and bicyclists.

Imagine how the failure of the Longfellow Bridge would have affected Boston and Cambridge’s commerce, and our collective psyche. How many lives could have been lost if it had fallen into the Charles River?